Reflections on musical notes from a green phone booth...

My tribute to a master

Green public phones have long dotted the Japanese landscape, as solitary sentinels, now remnants of an era when smartphones were still finding their way and communication relied on shared devices.

On a rainy evening in the early 90s, wandering through Japan, my ancestors’ land, longing for a few minutes with loved ones — connected through an imaginary line released in space — I headed to a phone booth, which was about to become a doorway to a lifelong connection.

Upon arriving at the booth, lifting the receiver, sliding in the phone card, and dialing the number, I waited for the line to go through. And there it was, in that pause just before the first ring: his music to greet me. It wasn’t just an on-hold melody; it was a pre-melody, an overture to a deeper harmony. I felt that as an embrace, as if I were back in my living room, sitting in my favorite armchair beneath the soft lamp glow. Although I only came to realize it much afterward, that evening, Japan started to build its way to my life’s journey, leading me to the understanding that home is not necessarily a physical place, but what one carries within.

For months, that sequence of notes I did not know until that green phone booth — now a memorable photograph of Japan — played in the recesses of my mind, intertwining with Tokyo’s daily cadence, almost like the city’s soundtrack.

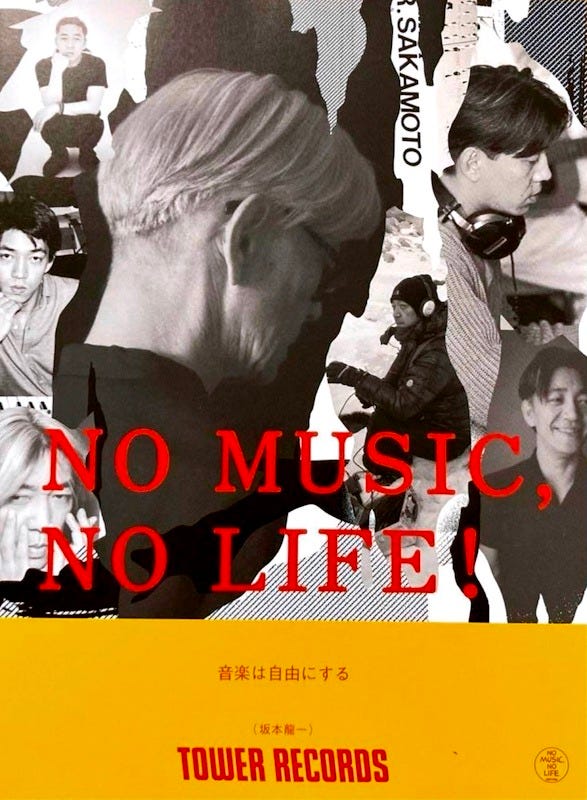

One morning, walking the streets of the Japanese capital, a poster of Antonio Carlos Jobim beside a charismatic Japanese man — who I would later discover to be Ryuichi Sakamoto — drew me inside a Tower Records store.

Being miles away from what was then my only home, Brazil, and stumbling upon a familiar face — even in a printed form, in such a foreign and public setting — instantly brightened the moment. The poster was not about any collaboration between the two maestros, as I had initially assumed; rather, it showcased Sakamoto’s great admiration for Jobim’s oeuvre.

It was then, while at the store and listening to an album by the gentleman who so humbly looked up to Jobim, that I made a happy discovery: those haunting chords echoing across the city belonged to “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” a piece as emblematic of its creator as of his homeland. Serendipity or not, that was the moment I crossed paths with Ryuichi Sakamoto, igniting an admiration for his work ever since.

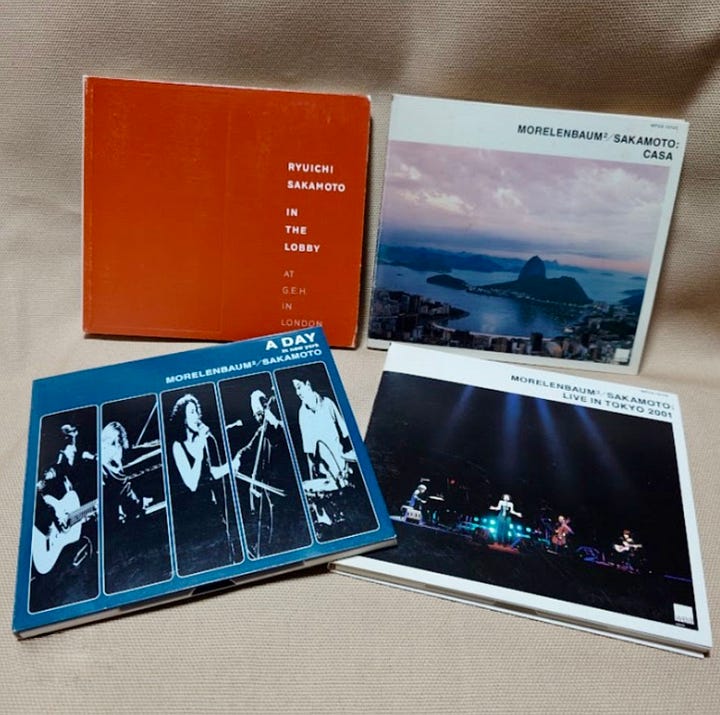

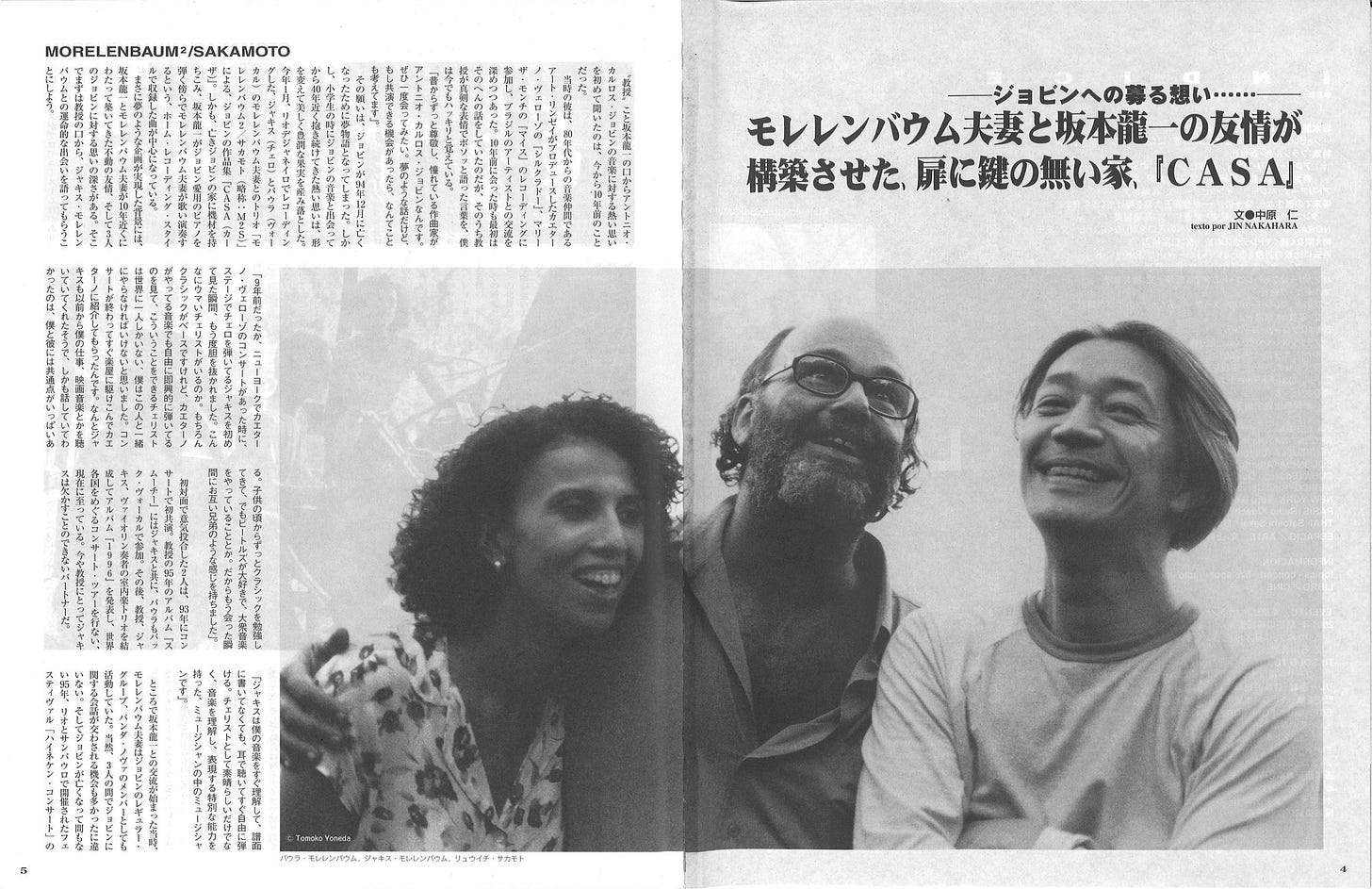

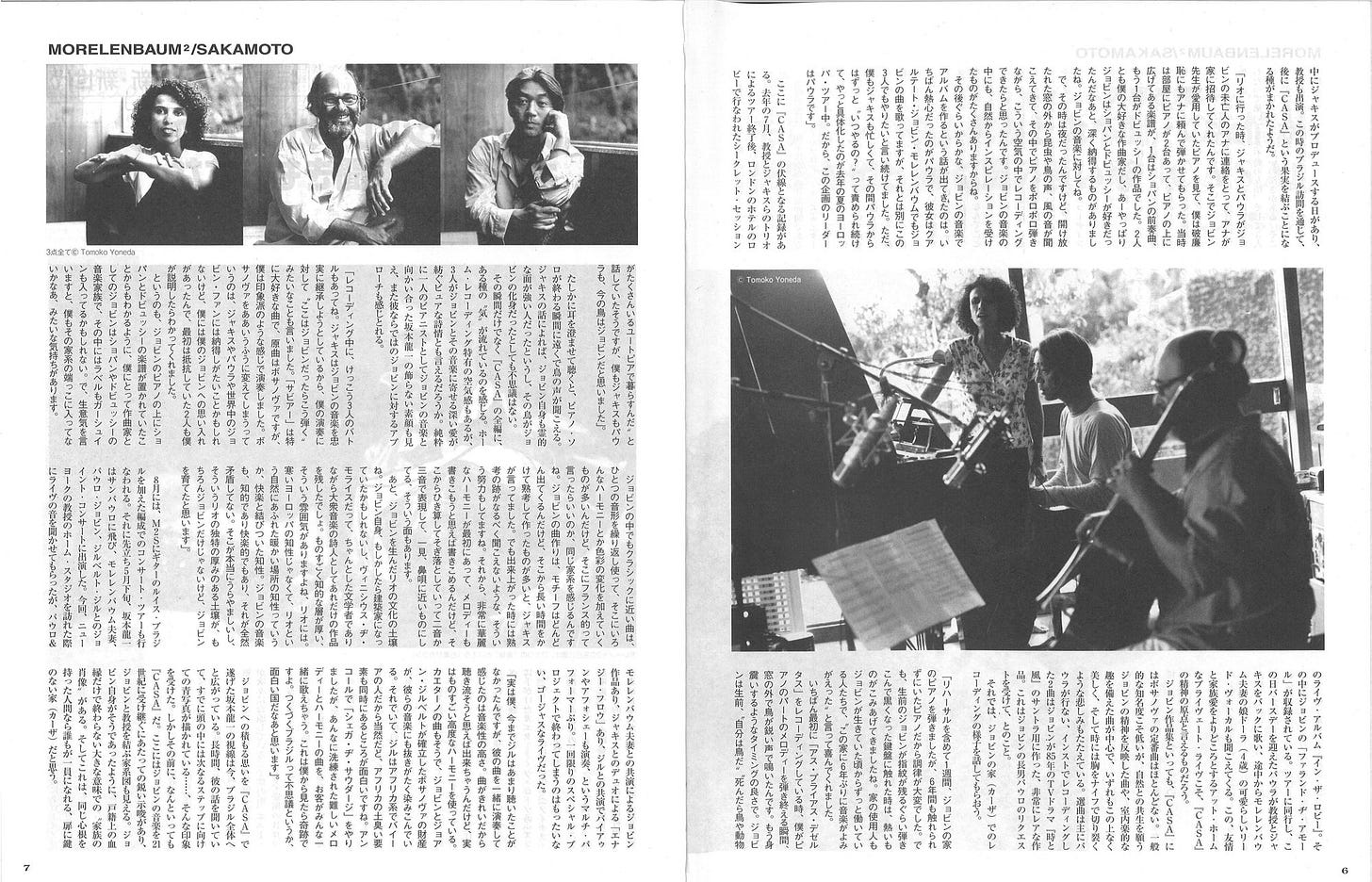

Years later, Sakamoto was scheduled to perform in Tokyo, with the Brazilian musicians, Paula and Jaques Morelenbaum. Still acclimating to the language, in a time when the internet was far from the ubiquitous resource it is today, I somehow came to believe the Japanese maestro was married to the singer Paula Morelenbaum. My ever-inclined-toward-literary-fiction-fertile-imagination, had even woven this as a romantic dialog tale:

— How nice this could be! An acclaimed Japanese musician “married in love and in music” to another magnificent musician, and to make it even nicer, a Brazilian one at that!

And my imagination went on:

— How did they meet? Could that have been at a Bossa Nova concert? Or what if Jobim played match-maker?

Well, that “once upon a time tale” stuck with me for quite a while afterwards.

Fast forward to my time living in Tokyo, fully immersed in the Japanese culture and its day-to-day rhythm, I learned a surprising fact from one of my students back then: Paula Morelenbaum was not married to Sakamoto, but to the cellist Jaques Morelenbaum. Because of their shared last name, I mistakenly believed the two Brazilian musicians were… siblings. I know… I couldn’t help but laugh at the storyline I had spun out over those years.

That aside, I’m not bringing it up to save face for having changed the pairs, but Jaques Morelenbaum’s work — especially the stunning soundtrack for the Brazilian movie “Central Station,” as well as “Choro, Chuva e Cello,” — has been a recurring presence in my personal narrative.

And this is my little cherished story about one of the most celebrated Japanese musicians to date, brought to me by a nostalgic green phone booth and two remarkable Brazilian musicians — three, in fact, for Jobim belongs here as a guiding bird master.

I had the opportunity to see Paula and Jaques Morelenbaum again, this time performing with Marcos Valle at Birdland in New York City in 2018, and the clear picture of the two playing together that night still strikes a smile.

Sakamoto was not part of that performance, but it felt like he was — a presence channeled through the two artists on the stage. Needless to say, the Morelenbaums have, somehow, come to feel like an extension of Sakamoto to me.

Reflecting on it now, I finally understand why I thought the Japanese piano player and the Brazilian singer were married: communion — the sacrosanct communion of musicians on stage. Communion stems from the Latin communio. Communicare, from which communio derives, traces to the Proto-Indo-European root kom-, signifying together or with, while -muni- relates to sharing or exchanging, and -o, a noun ending, indicates a state or condition. Here, expanding past unisons and imprinting belonging, comes music — a communion that reverberates long after the final note fades. Sakamoto, through his music, conjured a layer of crafted communion, composing not only the notes he played, but bridging within the space between them.

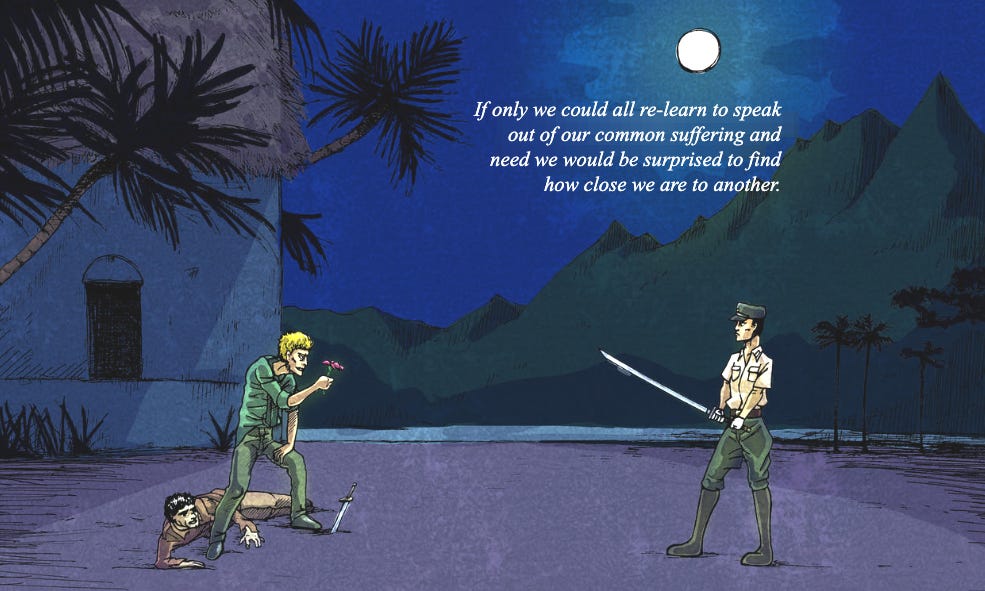

In 1983, director Nagisa Ōshima cast Sakamoto alongside David Bowie in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, a film based on Laurens van der Post’s novel, The Seed and the Sower — a memoir about his time as a prisoner of war in Java during World War II.

Without prior acting experience, and at just twenty-nine, Sakamoto accepted the role on the condition that he would compose the film’s score, which marked the true breakthrough in his experimental career. The track “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” specially, amplifies the story’s themes through plaintive strains that capture vulnerability and longing, exploring the tension between connection and isolation.

Yes, it’s a war film, but not in the conventional sense of battles and strategy; instead, it examines how rigid codes of honor, duty, and masculinity in military cultures create psychological prisons as confining as the physical camp. It suggests that love and compassion might transcend war, and yet also that repression — sexual, emotional, cultural — can twist into cruelty.

The plot centers on the relationship between Captain Yonoi (played by Sakamoto), the camp commandant, and Major Jack Celliers (David Bowie), a newly arrived British prisoner. Yonoi becomes fascinated — almost obsessed —with Celliers, experiencing what the film presents as a fatal attraction that the captain cannot understand or control. This obsession disrupts the camp’s rigid order and challenges Yonoi’s understanding of himself as a Japanese soldier committed to bushido (the warrior code).

The film’s title comes from a moment when Sergeant Hara (played by Takeshi Kitano), drunk, tenderly wishes Colonel Lawrence (Tom Conti) Merry Christmas despite them both being soldiers bound to opposite sides — laying bare the absurdity and tragedy of war, which forces man to deny their common humanity.

Oshima deliberately made the film ambiguous and uncomfortable, refusing to provide simple answers about cultural identity, or moral righteousness. It’s less about who wins the war than about how war damages everyone it touches, victors and prisoners alike. Tellingly, this is exactly what Sakamoto himself would dedicate much of his life to uphold: the fragile ties that hold us together.

Final years…

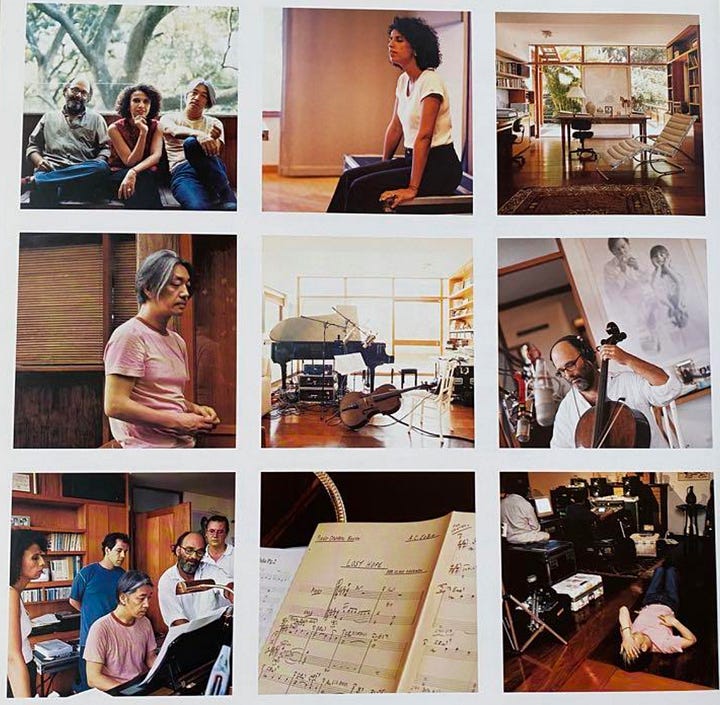

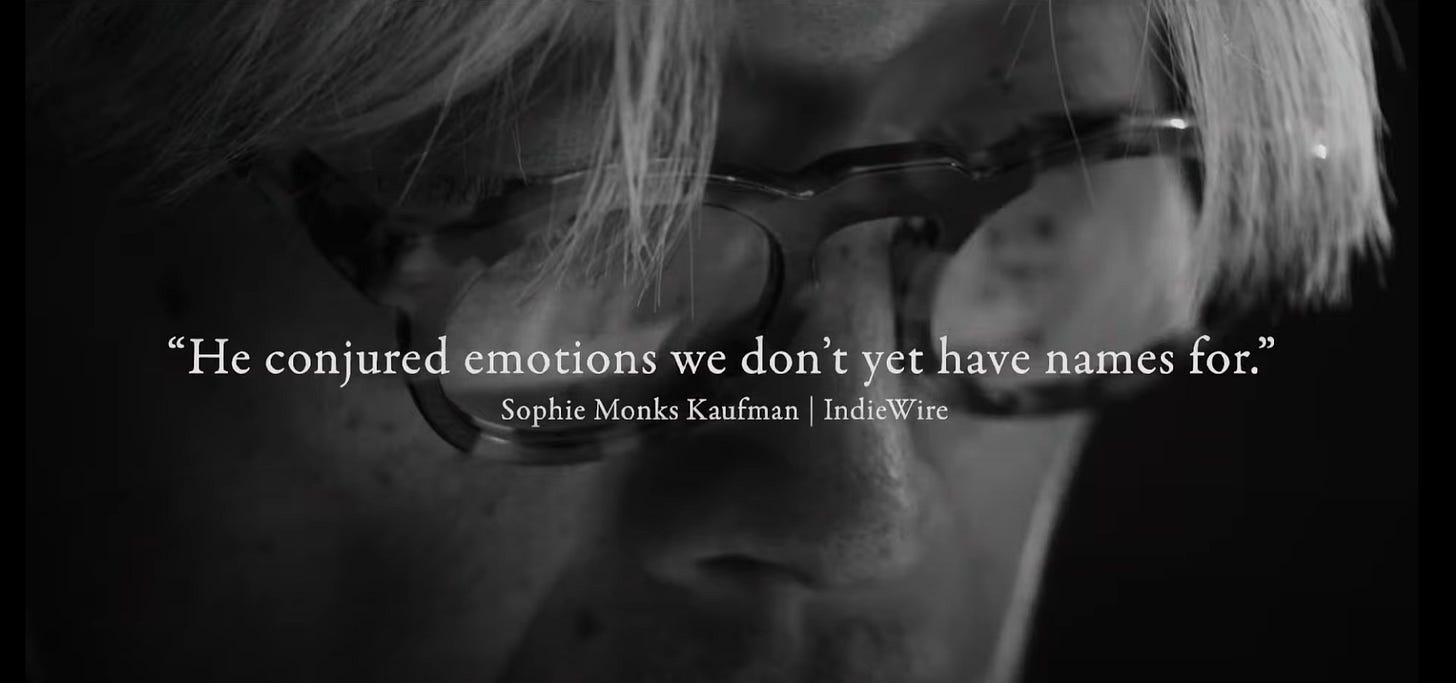

Following a major operation and a long hospital convalescence in early 2021 — the latest chapter in a struggle with cancer first diagnosed in 2014 — Sakamoto found just enough strength to sit before his synthesizer not intending to compose, but rather “to be showered in sound,” hoping it might mend a little of his “damaged body and soul.” From those tentative gestures came a series of sketches, recorded like entries in an audio diary across 2021 and 2022. Out of that tenuous span emerged the album 12 and, in its wake, Opus, the starkly poetic 2023 farewell film directed by his son, Neo Sora.

Filmed in September 2022 at Tokyo’s legendary NHK 509 Studio, Opus captures the composer’s last performance in circumstances that transform limitation into a redemptive meditation on mortality.

Too frail to play a full set in one sitting, Sakamoto recorded the program over multiple sessions across a week, with only the film crew as his audience, resulting in a masterful reimagining of a life’s work, where the performer’s impermanence becomes inseparable from the performance itself.

For the nearly two-hour film, his hands shape the sound on the keys — sometimes slowly — one pensive note at a time. More than a concession to physical necessity, the slower tempos were a conscious choice. Knowing it could be the last time he would present his art, he wanted — in his own words — “less notes and more spaces.” Slowing the tempo let each note linger in the air.

Curated and sequenced by Sakamoto, the twenty pieces performed in the film trace the arc of his career — some pieces, he had never played solo before; others, like “Tong Poo,” slowed almost to suspension, as if time itself were stretched into sound. Stripped to its very core, the music let each pause resonate, carrying the weight of a lifetime.

But what makes Opus stunning is the way it lays bare fragility. Where earlier performances were marked by flawless technical precision, here, Sakamoto wavers on some notes as he plays “Bibo no Aozora.” Sakamoto knew his days were numbered, and what we witness is his encounter with beauty and desolation, where Sakamoto captures how a soul perseveres even as the body withers.

In the film’s final moments, the piano carries on, its keys moving one after another, but Sakamoto is no longer there.

Sakamoto died in March of 2023, about six months after filming Opus.

Watching the last thing Sakamoto performed before he died — I feared — would feel like reaching an end with nowhere left to go. It would be too definite. Yet, the feeling Opus leaves you with is not one of grief, but of triumph. In many ways, Neo Sora’s film plays not as farewell but as the crescendo of a remarkable life and talent.

Since the Industrial Revolution, pianos have embodied the imposition of civilization on nature: machinery bending wood and strings into precise forms. Sakamoto once said, “we humans claim it falls out of tune”, and added: “that’s not exactly accurate.” For him, “when the instrument’s tuning goes awry, matter is struggling to return to a natural state.”

When I first went to Japan in those early 90s, I was trying to fit myself within a world of demanding expectations (whatever those expectations were) and was set on an inward search for a self I had yet to discover. It was also in Japan that my first forays into depression intertwined the giddiness of spring with new life challenges and the bittersweet beauty of becoming an adult away from home. So many dreams and longings were born back then — some that have been fulfilled; others, yet to be. In retrospect, thinking of “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” it makes sense that Sakamoto’s testament to the complex and shifting nature of desire would wind so tightly around me.

To you…

A Legendary Playlist…

Despite his reputation for serene composure, Sakamoto was not indifferent to how sound shaped public spaces — and he pushed back when music clashed with harmony. At his favorite New York restaurant, Kajitsu, he found himself disturbed by the jarring dissonance that clashed with its tranquil atmosphere. True to form, he responded not with detachment but with an email, written in equal parts honesty and affection:

“I love your food, I respect you and I love this restaurant, but I hate the music. Who chose this? Whose decision of mixing this terrible roundup? Let me do it. Because your food is as good as the beauty of Katsura Rikyu” — he meant the thousand-year-old palatial villa in Kyoto, designed on the aesthetic principles of imperfection and natural harmony known as wabi-sabi — “But the music in your restaurant is like Trump Tower.”

And that led to “Kajitsu”, the playlist shaping the morning soundtrack as I write from this café somewhere in the West Village, coincidentally, the same neighborhood Sakamoto called home. Everything feels in sync, cycling back and continuously.

“Because we don’t know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, an afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four, five times more, perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps 20. And yet it all seems limitless.”

—Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky (1949), later, in 1990, put into the motion picture directed by Bernardo Bertolucci and scored by Ryuichi Sakamoto.

“There is, in reality, a virtual me.

This virtual me will not age, and will continue to play

the piano for years, decades, centuries.

Will there be humans then?

Will the squids that will conquer the earth after

humanity listen to me?

What will pianos be to them?

What about music?

Will there be empathy there?”

— Ryuichi Sakamoto, 2023

Author’s note:

This humble essay is a scribble of personal memories shaped by Ryuichi Sakamoto’s influence on my life, originally written and published in March 2024, one year after his death, and later revisited as the same year approached its close, during a period of personal reflection and self-review of the year gone by.

Born in 1952 to the family of a book publisher in Tokyo, Ryuichi Sakamoto was a Japanese musician who reshaped the way the world understood electronic sound. Most know him in one of three ways: as the Oscar-winning composer of The Last Emperor; as a co-founder of Yellow Magic Orchestra, the band that helped invent techno-pop in the late 1970s; or as the haunting voice behind films like Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence and The Revenant.

But Sakamoto was far more than any single musical achievement. Beyond his music, he pushed boundaries toward what kindness and conscience could accomplish. A lifelong anti-capitalist navigating a commercialized world, Sakamoto remained committed to the role of art as a social and political vehicle, wielding capitalism’s own tools to amplify messages that defied its principles, turning even mainstream platforms into vessels for questioning and resistance. He gave his voice and resources to social and environmental causes: he founded the More Trees project for reforestation, co-created AP Bank to support renewable energy, and led global initiatives like Zero Landmine to clear the scars of war. After the 2011 earthquake, he organized the No Nukes concerts and helped form the Tohoku Youth Orchestra, believing children could rebuild their lives through music. He also spoke out against reckless urban development and challenged copyright laws that treated culture as commodity rather than community.

I have seen Sakamoto’s live presentations in Tokyo, Osaka, New York City, and São Paulo, and I wish I could have thanked him in person for what his generosity as a human being and artist has made me realize — that art can guide you home even when home feels out of reach, and its truest gift lies not in what it says but in how it teaches us to listen; that art is also the quiet shared, memory carried, and humanity revealed. And, perhaps, trying to make sense of all this prompted me to write this lengthy essay to trace, however imperfectly, the outlines of someone whose music reshaped silence within me.

If Sakamoto’s work has ever touched you — whether in a film score, a piano phrase, or in the quiet between sounds — I’d love to know which moment has stayed with you. What begins as something deeply personal often becomes unexpectedly collective, and, possibly, that is the truest tribute an artist like Ryuichi Sakamoto can receive.

Video credits:

* Video 1 - Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Ryuichi Sakamoto Trio, by VINCERO 빈체로

* Video 2 - Ryuichi Sakamoto & Morelenbaum² Casa Interview, by werdse12

* Video 3 - Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, analysis by Queer Plus Lotus

* Video 4 - Theme from The Sheltering Sky, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Opus Official Teaser (2023), by RyuichiSakamoto

* Video 5 - Ryuchi Sakamoto’s message + Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, by commmons

* Video 6 - Interview with Ryuichi Sakamoto (2012), by playonbarcelona

* Video 7 - Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda | Official Trailer, by mubi

Audio credits:

* Audio 1 - Kajitsu Playlist, by nytimes* Audio 2 - “As Ryuichi Sakamoto returns with ‘12,’ fellow artists recall his impact” | NPR - All Things Considered - produced by Elizabeth Blair, edited by Rose Friedman and mixed by Isabella Gomez Sarmiento.