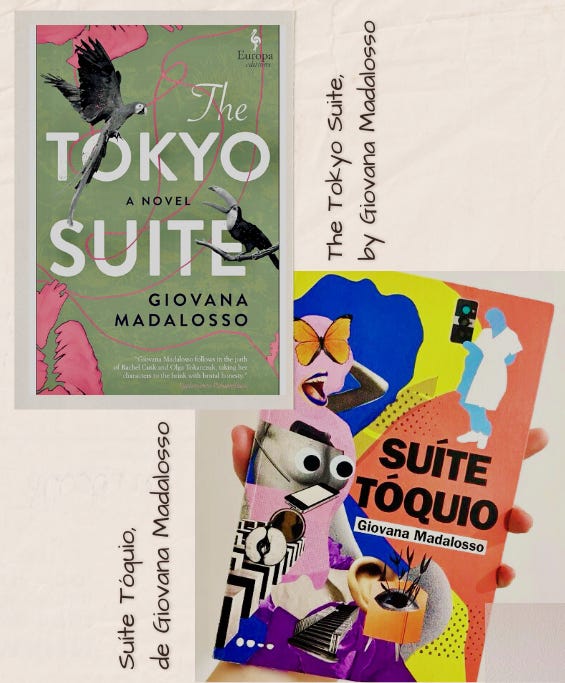

The Uncomfortable Mirror

Giovana Madalosso's "The Tokyo Suite" and the Economics of Care

This morning, ironically just a couple of days after the day established as our “international day” — for the world to see us, women, as women — I sat with coffee in hand, scanning the headlines, when I was arrested by a NYT review of a book that stayed with me long after I read the final page in its original language, Portuguese, years ago. Giovana Madalosso’s The Tokyo Suite has crossed the language barrier again, bringing its unflinching gaze, this time, to English-speaking readers. Seeing both editions side by side — one familiar, one new — I’m struck by how some truths about motherhood, power, and care need no translation. Beyond exploring maternal ambivalence, can intimacy exist within a fundamentally exploitative arrangement?

What happens when domestic fiction becomes socioeconomic critique? A child’s parents, who are largely absent, rely on a third woman to provide their child with love, routine, and emotional security. Yet, because she’s an employee, her role is inherently unstable — she’s indispensable but also disposable. This tension exposes the uneasy reality of domestic labor: those who raise the children of the wealthy often live with the quiet arithmetic of survival, calculating the cost of a roof overhead, meals on the table, and their own absence from home.

The story’s dual perspective — shifting between Fernanda, an television executive producer and Cora’s mother, and Maju, the family’s live-in nanny — operates as more than a narrative technique. It embodies the philosophical problem at the heart of contemporary caregiving: the irreconcilable conflict between the commodification of care and its essential intimacy. When Maju kidnaps four-year-old Cora, the girl who is hers in every way but law, she commits a radical act of love and resistance against a system that denies her legitimacy. And by reclaiming her agency through an indefensible transgression, Maju also violates parental rights and the implicit contract that allows the professional class to outsource its emotional labor while maintaining the fiction of primary attachment.

The rebellion extends further as Majú calls Cora her “Chickadee” — the intimate nickname of their quasi-maternal bond — and rechristens the child “Ana,” appropriating the privilege of naming and defining identity.

When motherhood becomes a divided, somewhat blurry role, what essential truth persists?

Consider how precisely Madalosso calibrates her characters’ motherhood instincts: both mother and nanny, 44, both untethered from maternal guidance, both navigating identity beyond traditional motherhood roles.

Love here reveals an act of sacrifice. For Maju, that sacrifice means risking everything — including living a life potentially interrupted by legal consequences. For Fernanda, her sacrifice emerges from a profound fragmentation — a woman who sees herself not as a subject, but as an object defined by external desires: her lover’s passion, her husband's pragmatism, her professional ambitions.

Both women are caught in distinct perspectives, blind to the consequences of their emotional derailments. Their roles, however, are not freely assumed but forged in absence marked by a system that transforms maternal bonds in a transactional framework, exposing how circumstance, not individual agency, determines who provides care and who purchases it.

Following this business exchange, the room named Tokyo Suite — which connects to the book’s title — evokes the distance between the Japanese capital and the elitized neighborhood of Higienópolis in São Paulo, Brazil, where Fernanda’s apartment is located. It crystallizes the novel’s central paradox: a space presented as a generous provision while actually serving as the architectural embodiment of the employer’s outsourced maternal obligations, allowing her to prioritize her own pursuits while easing her conscience about the arrangement. What seems like benevolence is, in truth, a polished facade to an arrangement that enables one woman’s success at the cost of another’s autonomy — a control confined to labor and extended into the most intimate aspects of life. Fernanda’s affair with Yara, a director of nature documentaries, charged with animalistic overtones and liberation from domestic constraint, stands in stark contrast to Maju’s “conjugal visits” from her partner, Lauro, carefully scheduled and monitored. Even in desire, the women remain separated by who controls time and space, illuminating in the narrative how ruthless capitalism determines who works and also who gets to want.

To this dilemma, there is no policy solution, no perfect balance between career and caregiving, no way to separate our economic structures from our emotional lives. Instead, we’re left with Fernanda’s belated recognition: To be a mother, you need to adopt the child after birth. This truth, though, arrives too late to repair what’s broken, serving not as revelation but indictment — an acknowledgment of privilege’s inertia.

Perhaps the disquieting force in my reading is how these two women implicates its readers. Those with sufficient resources to delegate care will recognize their own justifications in Fernanda’s interior monologue; those who have provided that care will feel Maju’s invisibility.

The dynamics within Fernanda and Maju’s shared existence prompt one to ask: what is the price — emotionally, ethically, socially — for the arrangements that make modern life and motherhood possible? And who, ultimately, bears the true cost? Work-life balance has become a commodity — highly sought after but rarely questioned.

Art is often mistaken for mere leisure, a quiet indulgence for when the demands of life subside. But this is a mistake. Literature and films, as well as other forms of art, exist not just to entertain, but for one to ask, to inquire, to analyze, to see through. Without art, the world would be stripped of meaning. We would not live, only endure — and in a world both unruly and unjust.

The Portuguese Nobel laureate José Saramago once remarked: “Writers make national literature, while translators make universal literature.” With Madalosso’s literature alongside Walter Salles’ recent Oscar triumph with I’m Still Here, Brazilian art is taking its rightful place on the world stage, and art, at the same time, is challenging us to look in the mirror, uncomfortable as that might be.

This is why art is also politics. So is language, because language is never neutral. Literature is composed by language — and language is political.

So, here is my take — The Tokyo Suite is not just another major hit in Brazilian publishing. It offers a compelling contribution to contemporary Brazilian literature. It’s literature, yes! — no doubt on that — but it’s also politics.

That said, literary work is considered so because of its artistic, narrative, and linguistic qualities — political engagement alone doesn’t make something literature. A novel can be apolitical and still be literature. Nevertheless, even the choice to avoid politics is itself a political act, because literature does not exist in a vacuum. Literature reflects struggles, ideologies, identities, sovereignty, labor, resistance, sexuality, religion, nationalism, poverty, wealth, ambition, fear, anger, envy, sadness, love, life, death, even silence… and the many other dimensions of human experience, all inherently tied to language, culture, and history — and all of which are shaped by power structures.

Who gets to mother, who gets to love, and who gets to belong are not private concerns, but political ones. To speak, to write, to name — none of it is neutral. Literature may not always be about politics, but, in one way or another, it is always influenced by it. And as Madalosso’s The Tokyo Suite leads me to conclude, failing to recognize this is not just an oversight. It is complicity.

If there’s one truth that resonates beyond all others in Giovana Madalosso’s unflinching portrait, it is this: The deliberate symmetry challenges us to confront “how circumstance, not individual agency, determines who provides care and who purchases it.” And in that recognition lies both our discomfort and responsibility.

Que bom encontrar você por aqui!!!!! 😊